Once upon a time, the workplace was where a young person would make their transition from childhood to adulthood. In the distant past, the workplace was the great outdoors and conditions for this transition were immediate and physical, often extreme. Up until around 1870, when the Industrial Revolution started to kick in, for the majority of the population the "workplace" was on a farm (or ranch) and the transition to adulthood happened at an early age. It wasn't uncommon for an 8 or 9 year old to know how to hitch up a team of draft horses or run a tractor and help plow the fields. Necessity often drove the need for young children to help on the family farm. Families lived and worked together. Children who worked on the farm, even at simple tasks like household chores, were helping further the success of the family. The effects were immediate and obvious.

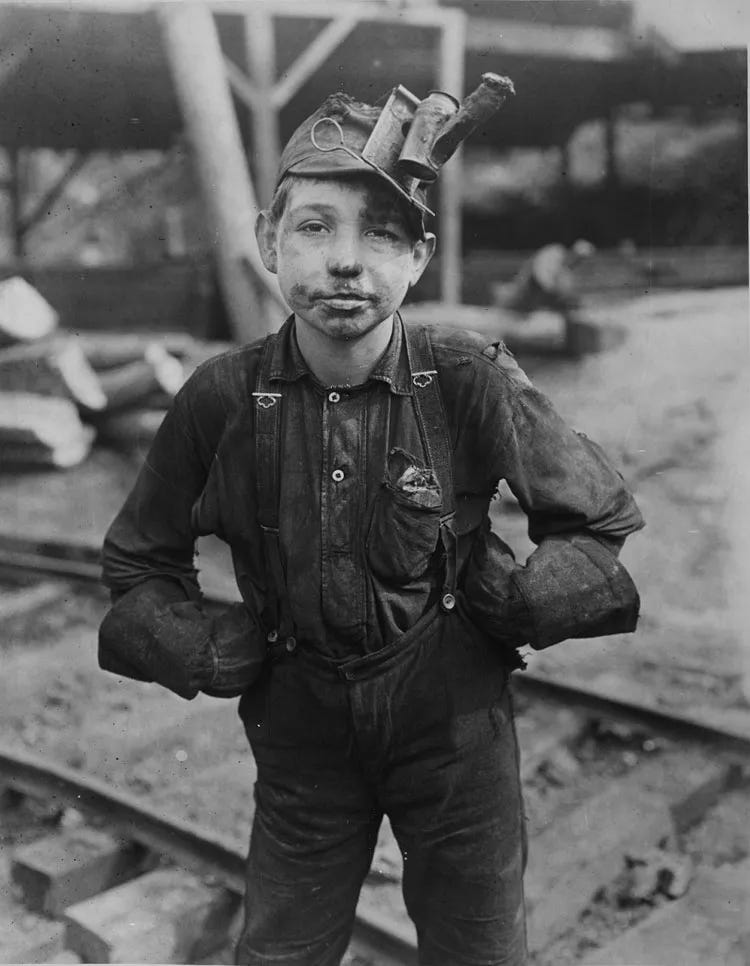

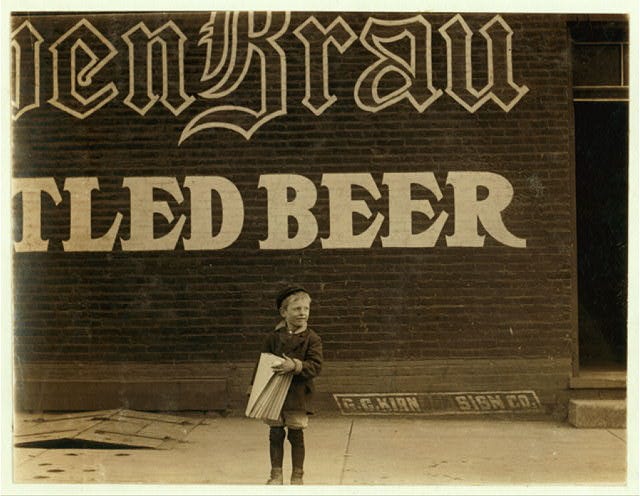

In urban or industrial settings, such as cities or company towns of the 19th and early 20th century, children of a similar age were put to work in retail stores, factories, and any number of industrial ventures. Families may have lived together, but they likely didn't work together in the way they would on a farm or ranch.

The urban workplace was little more than exploitation of other people's labor, including children, for the financial gain of a few. The wealth derived from labor was displaced in the industrial world. Factory and mining company owners saw their wealth grow without having to see the labor that created it while the factory worker saw little beyond a meager and predictable paycheck in exchange for the repetitive and often dangerous tasks that consumed their days. Greed more than necessity fueled the urban abuses of child labor. And while entire families may have worked at the same factory, they were separated from each other by factory spaces and repetitive tasks.

The golf links lie so near the mill

That almost every day

The laboring children can look out

And see the men at play.1

—Sarah N. Cleghorn

Whether rural or urban, children prior to the mid-20th century transitioned into adulthood an an early age. Things began to change for those born after WWII. It was the beginning of an unprecedented time of abundance and opportunity. As wages for working adults began to grow and standards of living rose, work for more and more children was becoming a choice rather than an obligation. Graduating high school and perhaps attending college was becoming the priority for children.

Next to the factory buildings filled with the noise of industrial commerce, a new structure appeared: The office building, populated by a new breed of employee. Known as "managers," they, too, were separated from the labor. The managed factory model was quickly adapted to education as all these new industries were going to need compliant factory workers. But this is a story for a different post.

To be clear, pressing young children into the industrial labor market wasn't a good thing. The child labor reform movement changed life for the urban child for the better whereas life on the farm or ranch still demanded all hands to pitch in when and where they could. (See The Short Life and Times of Cole Summers for a contemporary example of this rural work ethic.)

The shift away from challenging physical effort in the late 20th and early 21st centuries has altered how and when the transition from childhood to adulthood occurs. Today, the vast majority of children grow up in the world of cities, shopping malls, and deliver-anything-to-your-door services. (Want to buy some cocaine? There's an app for that!) Hard work has been separated - insulated, even - from the experience of transitioning from a childhood to adulthood. The duration for this transition is longer and completed later in life, if at all.

There are perhaps thousands of interacting and incremental reasons for this shift, more than I could possibly list or untangle. There are a smaller number of glaring symptoms, however, that suggest deeper interacting systemic issues driving the "failure to launch" phenomenon - an increasingly litigious society, helicopter and snowplow parenting, college campus culture that looks more like daycare and less like scholarship and truth-seeking, just to name a few.

By comparison, the young people I meet who have grown up knowing physical labor, particularly outdoors, seem to have matured in a way that those coddled throughout their formal educational journey seem to lack. What they know can be measured to a benchmark much closer to what a well-adjusted and satisfying adulthood is meant to be. Their "psychological safety" is defined by an internal locus of control, confidence is tempered by humility, and satisfaction defined in terms of needs rather than wants. They demand more of themselves, much more, then they do of others.

Today, many urban workplaces go to great expense to mitigate minute levels of discomfort and accommodate all manner of manufactured psychological distress. In short, modern urban workplaces are designed to perpetuate childhood. The immature and uncontested values, beliefs, and ethics of many 21st century knowledge workers are increasingly at odds with the values and principles of the Agile Manifesto. Workers who are allowed to hijack an organization's mission and bend it to their own goals are at odds with "Customer collaboration" and "Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer." Advancing personal agendas is at odds with "working together daily" and reflecting regularly together on how to adjust and collaborate more effectively.

The end result is that any workplace that caters to luxury beliefs, victim or identity culture, or any other infantilizing strength-through-weakness policy is destine for mediocrity. Implementing Agile in workplaces such as this will only help the organization become more efficient at mediocrity. The same fate awaits any individual who seeks to build a career in such an organization. If you sense you're one of the crabs trying to get out of the bucket, I suggest you learn what you can while plotting your escape and developing a strategy for finding a company where you can thrive.

Footnotes

1 Hugh D. Hindman, Child labor: an American history (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharp, 2002), p. 153.

If you have any questions, need anything clarified, or have something else on your mind, please use the comments section or email me directly.