The Dip and the Goal

"For those who want to learn, the obstacle can often be the authority of those who teach." - Montaigne

(This article is part of an on-going series dedicated to developing Agile mastery. Each post offers value to students on this journey, however, there is an advantage to those who start at the beginning.)

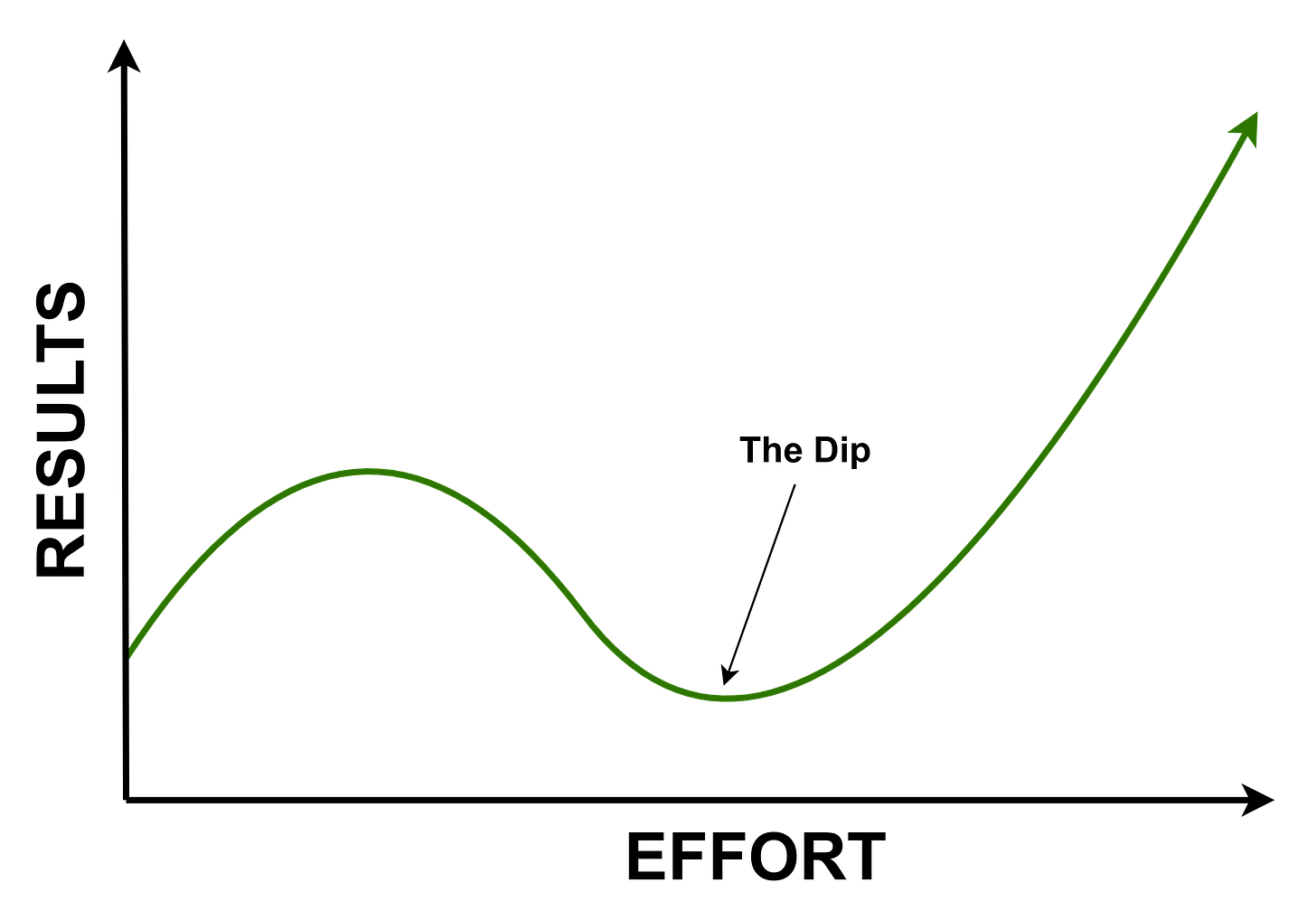

In his book, "The Dip," Seth Godin describes a common process we go through as we venture into new endeavors. It looks like this:

In Godin's words:

At the beginning, when you first start something, it’s fun. You could be taking up golf or acupuncture or piloting a plane or doing chemistry—doesn’t matter; it’s interesting, and you get plenty of good feedback from the people around you.

Over the next few days and weeks, the rapid learning you experience keeps you going. Whatever your new thing is, it’s easy to stay engaged in it.

And then the Dip happens.

The Dip is the long slog between starting and mastery. A long slog that’s actually a shortcut, because it gets you where you want to go faster than any other path.

"The Long Slog" could just as well be another book. There's a lot packed into that phase of the journey toward mastery:

Finding mentors

Study and research

Practice

Setbacks

Dues paying busywork

More practice

Thrills and chills

It's a lengthy list. In other words, it's a phase with intense activity with little or no visible or tangible results. Luck helps, but it won't get you through the dip. (Unless you get lucky.) You have to accomplish a myriad of tasks and reach an unknown number of smaller goals on your way through the dip. That's what makes working through dips so difficult.

If what you have in mind is an ambitious goal, there won't be just one dip. There will be dips within the dip. In all probability, there will be a series of dips as well as plateaus to work through. If knowing this excites you or fills you with a sense of resolve, you likely have what it takes to work through all that lies ahead. If it fills you with dread or otherwise turns you off, best quit now and move in another direction.

I've found all this to be true. But I'm a lazy bastard, so I'm always scanning for ways to make getting through subsequent dips easier and more enjoyable. A particularly effective combination of mental skills for doing this involves combining the idea of The Dip with a clear understanding of what qualifies as good enough and the Goal Gradient Hypothesis.

Goals and Good Enough

To expand upon an idea that G.K. Chesterton never wrote, "Anything worth doing is worth doing badly at the start," the most important thing in any endeavor is to start. But before you do, be clear about completing these three steps and commit to cycling through them at least three times, no matter how poor a showing you make on the first go.

Deliberately have as your goal to do poorly. Intentionally plan to produce something that is only worthy of throwing away. This is the first "good enough" measure.

Step away from the work - a few hours or a few days, but no more than that. During this time, reflect on your effort and identify one single thing you can improve when you return to the work.

As before, deliberately plan to do poorly, except for the one one thing you're going to do a little differently and therefore a little better.

As you cycle through these steps more times than you can count, it will become obvious to yourself that you've passed the "badly at the start" phase and are building momentum on your way toward creating something truly remarkable.

This tiny cycle builds in several important automatic behaviors. First is the skill for breaking down large goals into smaller, more easily achievable goals. The second is the habit of working in cycles of progress. Much like atoms are the building blocks of molecules, small iterations like this are the building blocks of progress. Atoms combine to form molecules, molecules combine to form larger proteins and fats which in turn combine to form organs and eventually an entire animal. Practicing to get a smooth tone from an open string on a cello leads to smooth tones on all the open strings leads to an overall smooth bowing technique that serves well for any note played on the cello. Practicing to get an even, paper thin curl of wood from a hand plane leads to a smooth plane technique on virtually any kind of wood.

This approach also begins to change your attitude about practicing. By building on a string of small success, when you pause and look back after a couple of weeks, you will begin to see how they accumulate into bigger and bigger successes. The Bach etude you struggled with several months ago now flows smoothly from memory, through your body, and into the instrument as you continue working on more and more subtle challenges. The rough spots on a table top yield to a few simple strokes of an expertly adjusted hand plane as you imagine how the stain will better reveal the grain pattern in the wood.

In short order, the very early "good enough" efforts are no longer good enough. In fact, your skill will have improved to the level such poor outcomes are no long possible unless you deliberately make them. A skill cellist has to consciously think about playing notes out of tune. Playing in tune is the default unconscious behavior. In this way, progress toward your goal, as measured by successively higher definitions of "good enough," begins to hardwire the new skills into your identity. Getting better at a skill changes who you are and how you define yourself.

Moving the Goal Posts

"[R]ats in a maze … run faster as they near the food box than at the beginning of the path." - Clark Hull

All that "good enough" stuff probably sounds elegant. So how can we make implementing an iterative approach to successive "good enoughs" easier? One technique I've found to be effective is to include the goal-gradient effect into how I define both my larger goals and the smaller "good enoughs."

The goal-gradient hypothesis was originally proposed by the behaviorist Clark Hull in 1932. Subsequent research by Ran Kivetz, Oleg Urminsky, and Yuhuang Zheng (2006) has shown what's true for rats in a maze is true for humans.

We found that members of a café RP [rewards program] accelerated their coffee purchases as they progressed toward earning a free coffee. The goal-gradient effect also generalized to a very different incentive system, in which shorter goal distance led members to visit a song-rating Web site more frequently, rate more songs during each visit, and persist longer in the rating effort. Importantly, in both incentive systems, we observed the phenomenon of postreward resetting, whereby customers who accelerated toward their first reward exhibited a slowdown in their efforts when they began work (and subsequently accelerated) toward their second reward.

Simply stated: As we get nearer to a goal, our desire and the effort we put into reaching the goal increase. Big goals have a longer lead up to the point at which the goal gradient effect kicks in and consequently require that we reach deeper into ourselves to muster the effort needed for The Long Slog as we work through medium and large dips. This is like, literally, running a marathon. Working through the pain of hitting the wall at mile 15 is harder to work with than the last 100 yards when the finish line is within sight.

Set Your Reward Checkpoints

"The best time to plant a tree was 30 years ago, and the second best time to plant a tree is today."

It's impossible for us to dedicate a 24/7 effort for years to achieve a high level of success with a skill. We die without sleep. So the end of each day can serve as a marker for establishing a good enough level of achievement, whether we work on our goal for 10 minutes or 10 hours. I've found that anything less than a day turns into a quagmire of busywork. Begin each day by establishing what the end-of-day good enough looks and feels like. Image the steps you take in the next several hours toward today's good enough. Imaging the feeling of getting close to achieving today's good enough.

Write. Them. Down.

Now...begin.

If you have any questions, need anything clarified, or have something else on your mind, please use the comments section or email me directly.

References

1 Kivetz, R., Urminsky, O., Zhen, Y. (2006) The Goal-Gradient Hypothesis Resurrected: Purchase Acceleration, Illusionary Goal Progress, and Customer Retention, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. XLIII, 39-58

Photo credit: From the wood shop.