Metaphors, Analogies, and Mental Models

Metaphors and analogies are good for explaining things in simple or familiar terms. Analogies help us transfer meaning from on subject to another or, more generally in the case of metaphors, create meaning out of a comparison.

Mammalian hearts work like a water pump.

A software application that works like a Rolodex.

Your eyes are like a camera.

Helen's personality is like a batch of warm biscuits - warm and inviting.

This works great, assuming you understand one side of the equation. If you know how a water pump works, you're going to have an easier time understanding mammalian hearts and vice versa. And if you've never met Helen but have been hungry in front of a batch of freshly baked biscuits, you're likely to have a good experience after meeting Helen.

Sometimes, however, people over extend metaphors and analogies. They get pressed in to service as mental models. Understanding water pumps isn't going to qualify me to diagnose heart ailments. And if Helen is having a bad day, her personality may be more like a bucket of wet hemp.

Mental Models are more generally valid, they apply to a number of situations. More than just the transfer of understanding and meaning, they help untangle issues and can help keep cognitive biases at bay. They also require more work to acquire and keep sharp. Over time, the savvy Agilist and seasoned Stoic are defined by how robust and resilient their latticework of mental models prove to be.

"The map is not the territory," is an example of a particularly hardy mental model. As framed by Korzybski:

A map is not the territory it represents, but, if correct, it has a similar structure to the territory, which accounts for its usefulness...If we reflect upon our languages, we find that at best they must be considered only as maps. A word is not the object it represents. ([1] p. 58)

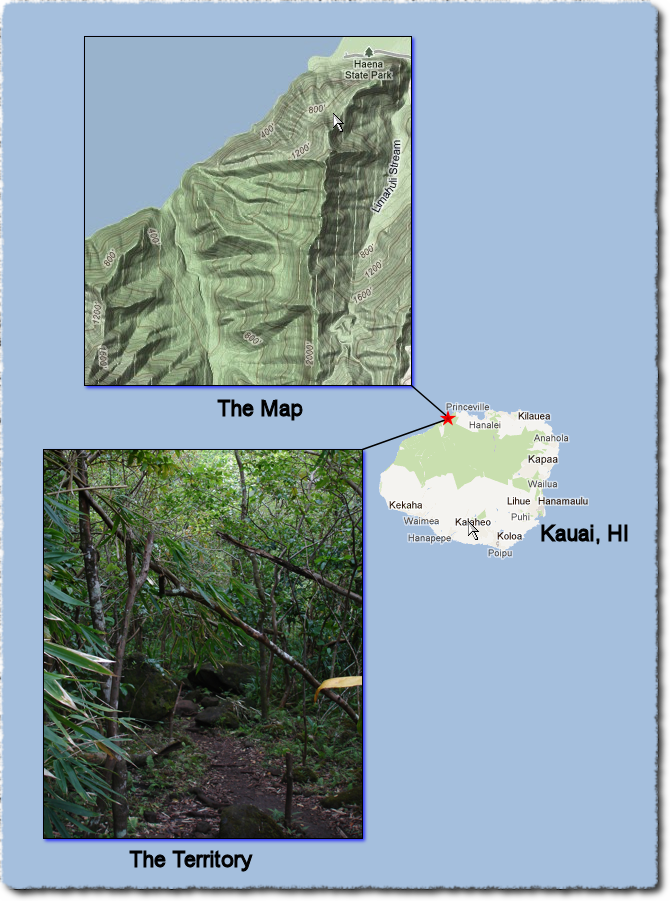

This seems obvious, but it's just a phrase until the owner has had a chance to use it on real-world problems. Far too many people operate as if the map is the territory. To illustrate, I'll start with a literal map/territory example (see Figure 1).

I've been to Hawai'i many times, and every time I go, I spend time on the North Shore of Kaua'i, hiking the Kalalau Trail. It doesn't look like much if you look at a high level map of the Island. Doesn't even look like much if you look at the topographical map of the trail which includes Hanakapiai Beach and the Falls. But looking at an actual photograph of the territory begins to reveal why it is this trail is frequently included in the top 10 most difficult trails. It is rainy, slippery, rocky, steep, and hot. That's the territory, and except for geographical references and elevations, it bears little resemblance to the map.

It's common to become frustrated when things don't go according to plan, when real-world experiences don't match the map we have in our head. Those with a growth mindset figure out how to update the mental map, learn from the experiences, and move forward. Those with a fixed mindset often become angry and look for someone to blame.

The map is not the territory.

There are many kinds of maps. What about the map you have in your head used to navigate the political landscape at your place of work? Or the map for raising your children? In Seeing vs. Visualizing I described a skill I learned for evaluating attackers.

The ability to rapidly assess an attack and visualize where it was going made it much easier to position myself to employ the most effective defensive technique. I recall deliberately thinking about my opponent as a giant molecule undergoing state changes. But there were numerous distractions that needed to be removed from the visualization which were irrelevant to the situation, such as race, gender, bulk (muscle or fat), and even clothing. Eventually, the skill developed such that attackers now look something like the image in Figure 2.

This, too, is a type of map, every bit as useful as the topographical map of the Kalalau Trail. There's a difference, however. The direct experience with the Kalalau Trail informed the map inside my head for "Kalalau Trail" by adding to it. The map for evaluating an attack was also improved by direct experience, except experience helped me to remove details that were unhelpful. The mental Kalalau Trail map was improved with details, the mental attack assessment map was improved by removing details. In both cases, the maps became increasingly more useful.

Even so, the map is not the territory.

Keeping the mental model "The Map is not the Territory" in you mind as you navigate a new situation is particularly useful as it will keep your mind open and searching for the information you need to build the map you need. If you stop at "This new job is just like a water pump," well, then your toast. Metaphorically speaking.

But this isn't where the work stops. Indeed, building out a latticework of mental models is just the beginning of a never-ending process of improvement and maintenance. The territory changes by the second. Maybe not by much, but the change is relentless. Eventually, your maps will become out of date. Usually in surprising ways. They must be tested, evaluated, and re-calibrated intentionally.

Photo by Joshua Rawson-Harris on Unsplash