(This article is part of an on-going series dedicated to developing Agile mastery. Each post offers value to students on this journey, however, there is an advantage to those who start at the beginning.)

WIIFM

You cannot not make decisions. And for better or worse, your decisions will have outcomes. So the questions are: Will you make good or bad decisions? Will you get the outcomes you expect or be surprised? Read on to learn how you can clarify your thinking about decisions and outcomes and what going slow to go fast looks like.

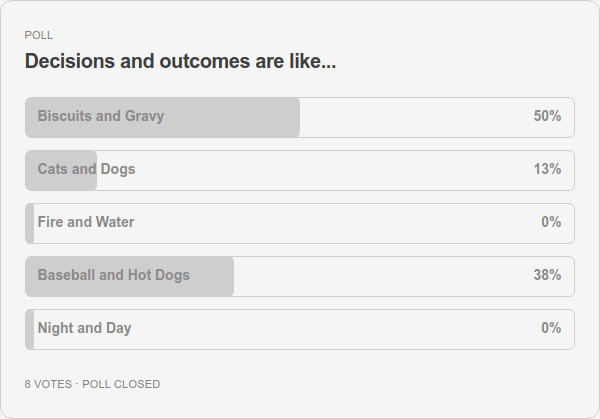

A couple weeks back I ran a poll asking readers to select a simile for "decisions and outcomes." Also, a poll so small it's a nano-poll. Nonetheless, here are the results:

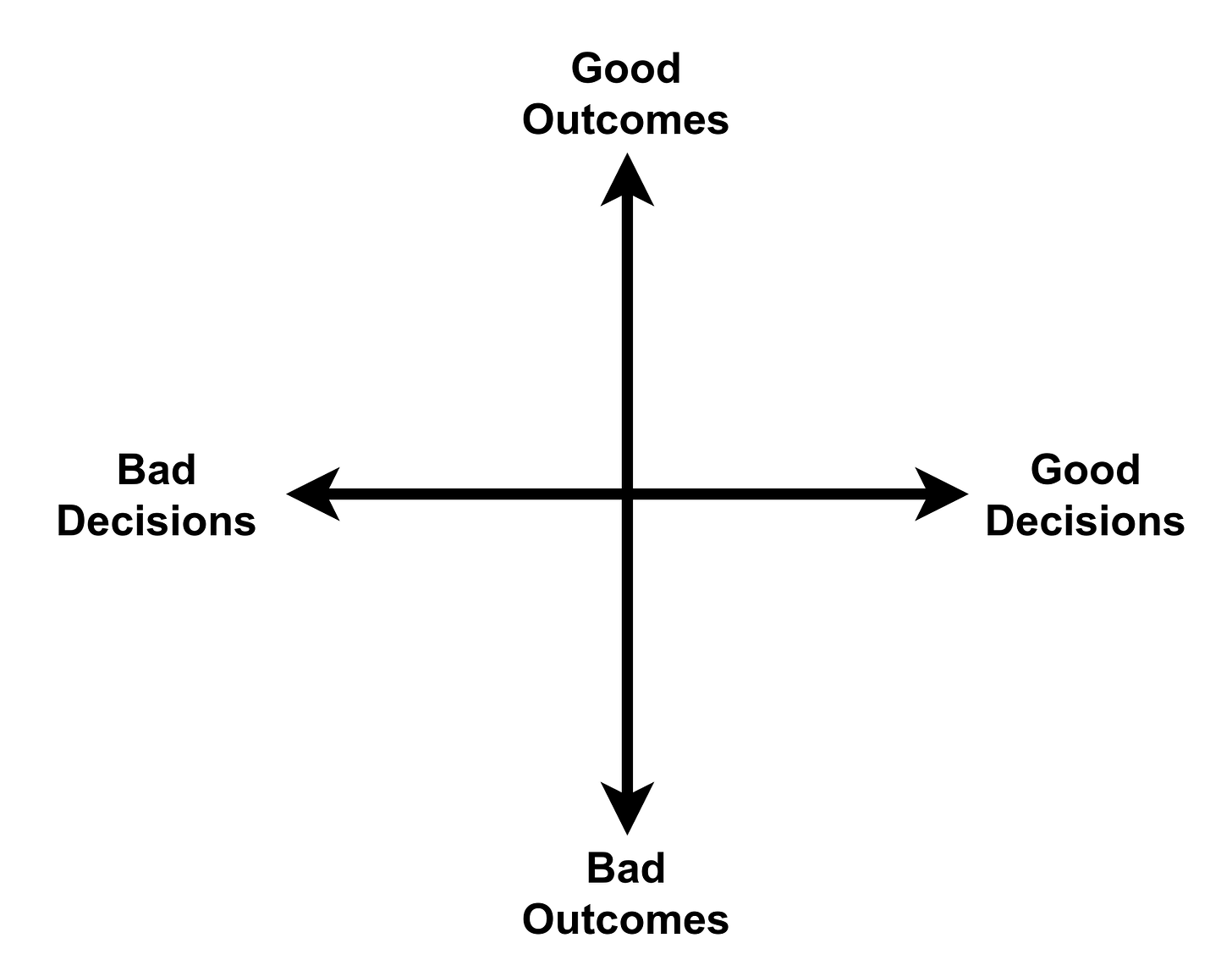

88% of the respondents (that sounds more impressive than "seven people") responded in a way that suggests decisions and outcomes go together. Only 13% (again, much more impressive sounding than "one person") responded in a way that suggests decisions and outcomes are different. Well, 13% of the respondents are thinking about decisions and outcomes in a way that is likely to lead to better decisions, more predictable outcomes, and ultimately greater success. Whether something is a good or bad decision is different from the outcome of having made a particular decision. Consider this matrix:

Four generalizations can be made from the poles.

Good decisions can have good outcomes.

Good decisions can have bad outcomes.

Bad decisions can have good outcomes.

Bad decisions can have bad outcomes.

We make decisions, but we predict outcomes.

We can collect terabytes of data that support our decisions. But outcomes can't be known with 100% certainty. The best we can do is calculate the probability of one or more outcomes. We make decisions, but we predict outcomes. No amount of data mining, wishful affirmations, or language of certainty can guarantee any particular outcome. Decisions and outcomes mix like cats and dogs, like fire and water. (Can't say for night and day. There's an interdependence and a certainty between the two.)

Parsing decisions and outcomes in this way makes it clear(er) that the skills for quality decision-making are different than the skills for quality outcome prediction. As an example, the former requires a lot of domain expertise whereas the latter requires familiarity with statistical analysis and systemic thinking beyond first order effects. There are many other differences and skills that could be called out, but you'll never find them, much less practice them, if you don't understand that decisions and outcomes are different critters.

For me, the lessons that sorted out the differences between decisions and outcomes came while working toward my undergraduate degrees in biochemistry and cell biology. The knowledge acquisition part of science affirmed the cause and effect structures behind what was known. But it was the actual practice of hands-on science, of designing and running experiments, that revealed the difference between decisions and outcomes.

One example among thousands: I was working in Professor Ray Fall's CU Boulder lab and tasked with growing and harvesting cultures from 200+ species of yeast. It was an involved process with hundreds of steps and parameters that needed to be carefully measured and closely monitored over several weeks. The tail end of this process required the yeast to be dehydrated via a vacuum process. All set to dehydrate my first batch of 10 cultures, I turned on the vacuum and all 10 test tubes promptly imploded, contaminating the harvest with glass shards. Vacuum too strong and glass too brittle. Lots of good decisions, two hidden parameters, one very poor outcome. (I'd like to bookmark something here. This was what Amy Edmondson would call an intelligent failure. This may have been a bad outcome, but the experiment was a success in that it revealed the hidden parameters.)

All the decisions made in this process were good decisions. (The two hidden parameters were non-decisions.) The outcome was bad. Rather than toss out all the decisions - the entire process leading up to the harvest - I repeated all the previous decisions and add two more related to the vacuum and test tube strength. The same decisions (+2) lead to the predicted and desired outcome.

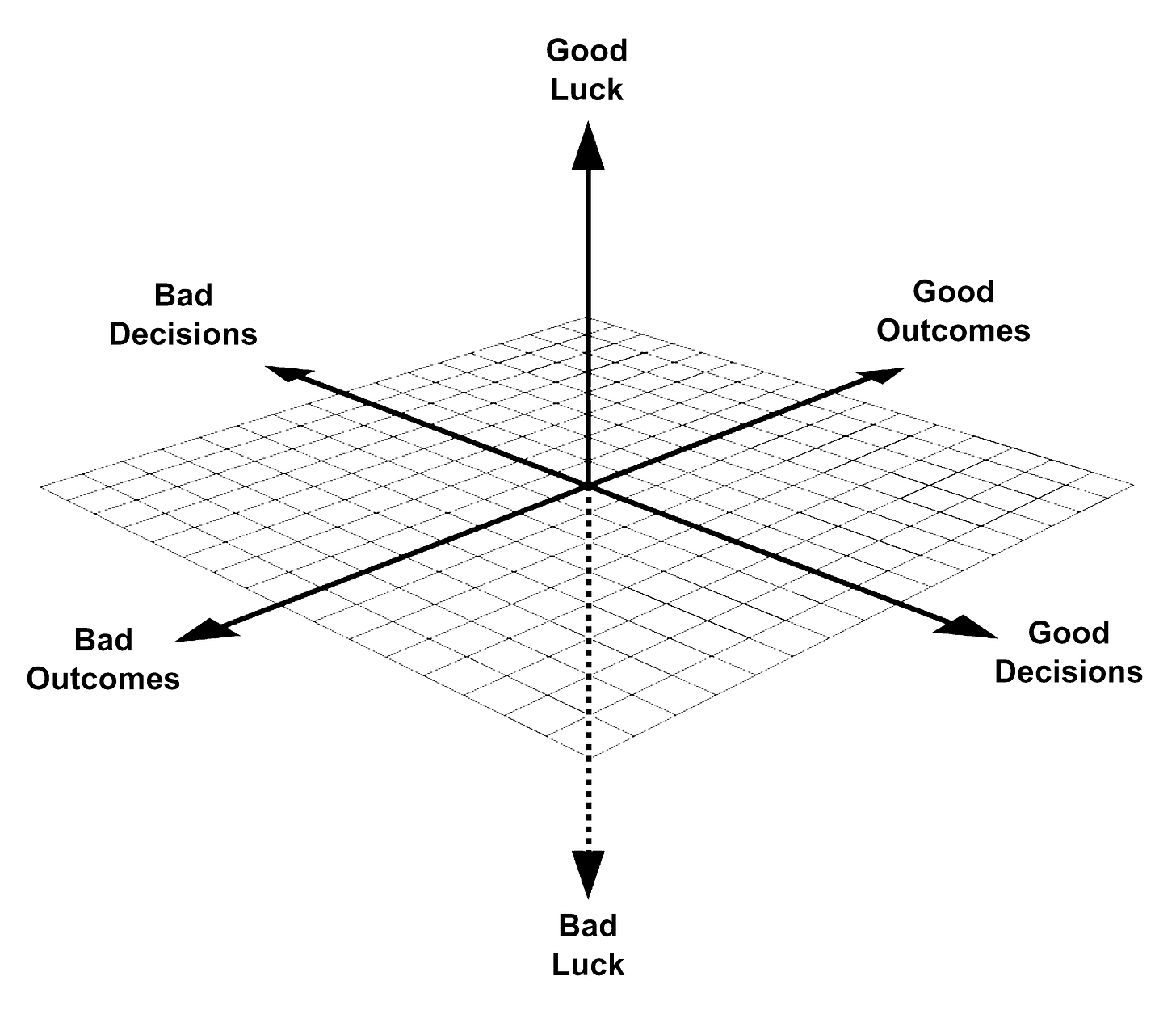

A third and especially useful dimension can be added to the decisions/outcomes playing field: Luck.

The possibilities:

Good decisions with good luck can result in good outcomes.

Good decisions with bad luck can result in good outcomes.

Good decisions with good luck can result in bad outcomes.

Good decisions with bad luck can result in bad outcomes.

Bad decisions with good luck can result in good outcomes.

Bad decisions with bad luck can result in good outcomes.

Bad decisions with good luck can result in bad outcomes.

Bad decisions with bad luck can result in bad outcomes.

One new dimension, twice the number of possible interactions between decision and outcome. Let's add a fourth! Ack. Let's not but say we did. That would lead to 16 possible interactions. The possibilities grow exponentially as dimensions are added. Math aside, all you need to know is: "Making good decisions can be hard." Let's stay with three dimensions for the time being.

Luck is an important yet mostly unexplored dimension in decision research. Probably because it's extremely difficult, if not impossible, to define. You can, however, reduce the amount of luck involved with any decision. Returning to my yeast farming experience for a moment, if I simply followed my hunches for how to grow and harvest hundreds of yeast species and relied on luck to show me the way, it would have taken considerably longer to reach a successful outcome. Less then the amount of time it would take 100 monkeys randomly tapping on 100 typewriters to recreate a Shakespeare sonnet but longer than the grant money for the job would last.

The fast path to success was achieved by a lot of slow progress at the start to understand why each step was necessary and how each step interacted with the system. The more I understood, the less influence luck had - good or bad - on the outcome. The more I squeezed luck out of the process the easier it became to predict the outcomes. In the end, I had a reliably replicable process for growing and harvesting a wide variety of yeast species.

I have not found an area of interest in life that doesn't benefit from this approach. There are, of course, a few important levers to move and dials to watch. It's possible to pursue this approach beyond what is useful or desirable. The nature of the effort and circumstances will often dictate how much time and effort is spent on chasing down details and rounding out your understanding. Remember that exponential business hinted at earlier? Tracking down too many details can be just as bad as not tracking enough. The trick is to select the most influential two or maybe three.

While working to harvest yeast, I was bound by the scientific process for knowledge and understanding. This demands a high level of rigor and thoroughness. When working out the perfect recipe for palak paneer, I'm going for highly subjective criteria like taste and texture. Before you begin figuring out your path from decision to outcomes, answer the question: "What am I optimizing for?" While engaged in working out the process, regularly ask yourself: "Am I there yet? Is this good enough for now?"

Regardless the path you take, the decision is yours. Chose wisely.

If you have any questions, need anything clarified, or have something else on your mind, please use the comments section or email me directly.

Photo by Norbert Braun on Unsplash