Beliefs, Torsion Boxes, and Change

"Of course not. After all, I might be wrong." - Bertrand Russell’s response to being asked whether he’d die for his beliefs.

For over ten years I've been wanting/needing/avoiding making a particular tool essential for building shoji screens and kumiko: A torsion box. Basically, it's a super flat and rigid surface for building things that need a super flat and rigid reference on which to assemble the parts. The thing is, they take a lot of effort, time, and space to build. And - for the size I need - they're freakin' heavy.

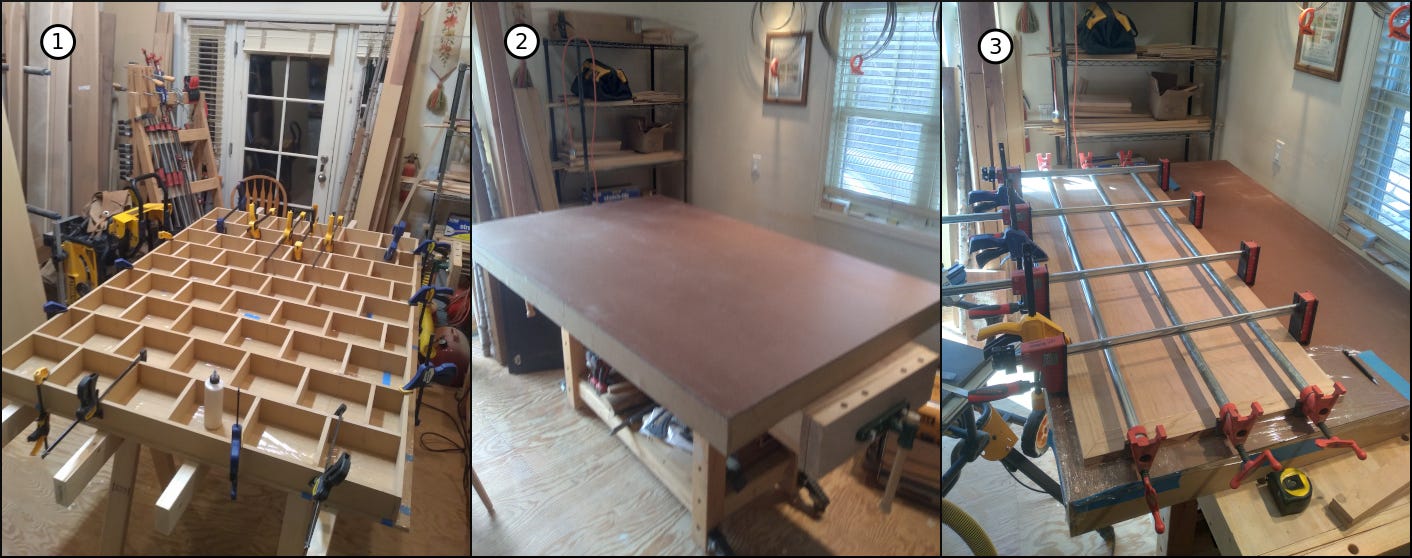

After two weeks of designing, measuring, planning, measuring, preparing, leveling, measuring, cutting, leveling, gluing, and nailing the freakin' heavy torsion box is done.

Mid-project, zero shop space available.

Torsion box, ready for service.

Doing its thing. Holding half a table top flat while the frame glue dries.

Elbows deep into this project I had to remind myself why I was going to all this trouble. I thought of all the future projects that will go much easier with a torsion box. Few things are worse than working on a sizable project - say, a table - only to have the thing turn out lopsided and uneven.

And of course, my mind wanders like a six month old puppy when I'm in the woodshop and I began thinking about other things that are useful because they provide a stable and level reference point for building other things. Beliefs, for example.

Unlike beliefs, though, claims about the flatness of my torsion box can be objectively verified to the satisfaction of virtually all woodworkers by any number of tools and devices. If my build reference is garbage the wobbly and warped end product will reflect that legacy. There’s no hiding from the fact. What I put out into the world from my woodshop will be the trustworthy testament to my skill and the truth of my claims.

Similarly, we use beliefs to build our model of the world. We use beliefs to build other beliefs. And yet, we have no way to objectively verify - for ourselves or others - whether our beliefs are on the level and true. In fact, we seem to have an ever expanding set of cognitive tools and devices for convincing ourselves that our beliefs are level and true even when they are as twisted and gnarly as bristlecone pine.

Not that there's anything particularly wrong with having an odd collection of beliefs. Bristlecones are well adapted to their environment and live a long time. But they're also very rare. In the human cognitive world, many brilliant people - particularly artists - have a curious set of beliefs to those of us living outside their internal world. Thank god for the outliers, they help keep life interesting.

To each their own, I say, as long as you're the only one who will pay the price for holding untested beliefs. And if you end up reaping great rewards for the beliefs you hold, congratulations and enjoy! Where things get tricky and sticky, however, is when someone with idiosyncratic beliefs occupies a position of power and influence over others, whether it be a family, company, or governmental position.

For my woodshop torsion box, I watched a lot of videos, read a lot of articles and forum posts, considered a lot of different materials, and sketched a bunch of drawings in preparation for what I wanted as an end result. I ranged far and wide to acquire the best understanding possible for how to build a torsion box. The prep-work felt like the work I do researching something I'm interested in writing about. And, like the planning and materials selected for the torsion box, the planning and data I survey for any particular topic ultimately defines how I craft the published article. Same for settling on what I believe about myself and the world.

If we want our beliefs to serve us in a way that is healthy and reliable, we have to test them. Frequently. No matter how hard I really, really want light-weight balsa wood and tissue paper to serve as a reliable torsion box for building furniture, it's isn't going to pass muster and will undoubtedly collapse on first use. And no matter how hard I really, really want data to conform to my hypothesis, opinions, and existing beliefs, in the end the quality and depth of my research will determine the shape and quality of any resulting beliefs I may hold. Weak data and reasoning behind an argument, plan, or belief means it will collapse when reality marches through with it's clumsy indifferent boots.

Whether building a torsion box or a belief, if any bit of it is out of alignment during the building process, then the end result includes the misalignment. Anything built on top of such a misalignment will also include this fault. Each misalignment allowed into the torsion box or belief will imperceptibly, yet incrementally and cumulative, lead to twists and bends that leave it misaligned with what's true and level. All other actions based on such a box or belief will skew away from my ultimate goal of building beautiful things (or living a good life or happiness or peace of mind.)

If all the rest is common coin, then what is unique to the good man? To welcome with affection what is sent by fate. Not to stain or disturb the spirit within him with a mess of false beliefs. - Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 3.16

The ethical and healthy response to misalignment is to acknowledge something doesn't fit. As Marcus writes, accept the discomfort fate has exposed as a blessing, as a signal something isn't quite right. How fortunate that you would be shown this weakness before such a time you might rely on it's accuracy, that you have an opportunity to correct the problem before it causes you or someone else harm!

So I work to understand why the pieces of life don't fit or feel quite right. And I keep going until the facts align - either with additional or better data or because my understanding has shifted and my measurements about the world are adjusted. Understanding the limits of wood has taught me to understand the limits of data. It's an understanding requisite for building resilience and value - whether it be furniture or beliefs about self and the world.

The similarities between torsion boxes and beliefs end here, however. My box is done. Changing it's alignment is limited to a bit of sanding here and there. Beliefs and the models of the world we build from them change through time, most often without our awareness or effort. Choosing to be an active participant in this process is a truly transformative act. The path to mastery, satisfaction, and peace of mind involves constantly choosing a growth mindset over settling for a fixed mindset.

Addendum

A few of the questions about beliefs I regularly ask myself...

Origin and Scope

How are beliefs created?

What are my beliefs about myself? About the world around me?

How can I know if I created the beliefs I have or if they were inherited from others? If they came from others, are they a gift or an infection?

Purpose

What's the original purpose behind each of my beliefs?

Do they still serve their original purpose?

Is their original purpose still worthwhile?

What kind of world have I built from my beliefs?

Do my beliefs define a level reference point for building a healthy, robust, and resilient model of the world?

Change

How can I identify the unintentional imperfections built into my beliefs?

How hard is it to change my beliefs? What does it take to evolve them? Bend them? Break them?

If you have any questions, need anything clarified, or have something else on your mind, please email me directly.

Photo credit: Bristlecone Pine Forest of the White Mountains in California, Wikipedia.