WIIFM

How do you think about the space in which you move - the way it affects you and vice versa? And what about mental space? What happens to your mental and physical spaces if they are neglected…or exploited? Read on to explore a few contemporary trends and the profound affects they have on your physical and mental spaces.

[Note: This article is long, so your email client may not handle it correctly. You can read it at the Substack website. Click on the title in your email to go to the article directly.]

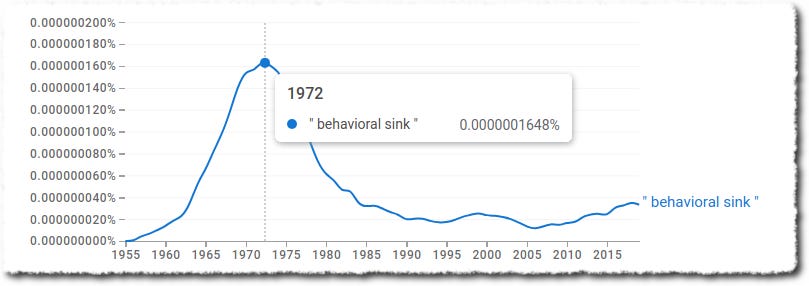

The term "behavioral sink" is attributed to the behavioral scientist John Calhoun and dates back to the late 1950s. The phrase describes a phenomenon Calhoun observed in his experiments designed to study the effects of social density on the behavior of mice and rats. Using carefully designed, yet confined spaces and eliminating various natural environmental constraints - such as adverse weather, scarce food and water, predators, and diseases - Calhoun observed patterns of emergent behavior over multiple generations as the populations of rats or mice grew in each of the controlled environments.

As the population density increased and became overcrowded, Calhoun (1962) described the results:

The consequences of the behavioral pathology we observed were most apparent among the females. Many were unable to carry pregnancy to full term or to survive delivery of their litters if they did. An even greater number, after successfully giving birth, fell short in their maternal functions. Among the males the behavior disturbances ranged from sexual deviation to cannibalism and from frenetic overactivity to a pathological withdrawal from which individuals would emerge to eat, drink and move about only when other members of the community were asleep. The social organization of the animals showed equal disruption. Each of the experimental populations divided itself into several groups, in each of which the sex ratios were drastically modified. One group might consist of six or seven females and one male, whereas another would have 20 males and only 10 females.

The end-point of this pattern of emergent behaviors as population density increased is what Calhoun referred to as the "behavioral sink." After a burst of interest in the 1970s in both the scientific and popular literature, use of the term slipped into the background.

Calhoun was challenged, I think rightly1, for his tendency to anthropomorphize his research and suggest that what was observed with mice and rats applied to human populations. Alexander's work (1979) on social interaction and addiction during the 1970s has been similarly overstated, mostly by non-scientists. However, I also agree with others that many of Calhoun's ideas for how to re-think issues around population density with humans were underappreciated. In later research, he discovered that the pathologies exhibited in his rodent populations could be mitigated by improvements in how the experimental environments were designed and built. Redesigning spaces in which we educate our children and the workplaces for knowledge workers is something that only now, post-pandemic, is receiving creative thought and experimentation.

Edmund Ramsden and Jon Adams (2009), writing about Calhoun's later work, had this to say:

Calhoun challenged directly the “dismal theorem” of Paul R. Ehrlich in which each additional human was perceived as having a negative impact on the environment. Man was a “positive animal,” for whom the pressures of density had driven innovation and social complexity, leading to a division of labour and new social roles. Thus, as physical space declined, man was forced to extend his “conceptual space”—the network of ideas, technologies—enabling more efficient use of resources while ensuring that each individual maintained a limited number of meaningful social interactions. This allowed for increased population growth, with the process governed by a series of positive feedback mechanisms. There was of course a limit to both numerical and conceptual growth, beyond which our social and physical infrastructure would be overrun, but if the population were to be stabilized at the present density, human potentiality would stagnate: “every role vacated will be filled precisely by a similar one. Such stability and predictability have rarely been the way of evolution over any protracted period of time. Stable products rarely last.” Our conception of “utopia” as an environment in which the basic requirements of the population were met and social hierarchy obsolete, failed to account for social, biological, and psychological needs: the border between utopia and dystopia was not merely fine and easily crossed, it was fictitious. As he stated in an interview: “Human beings thus face a predicament: If we try to make everybody totally happy, we’ll destroy mankind.” (Emphasis added)

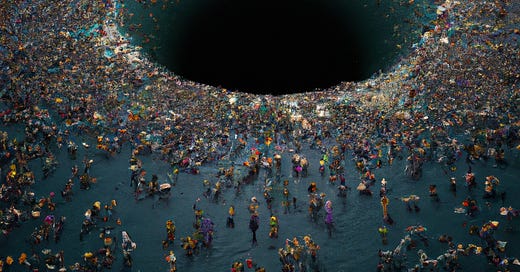

Speculating that Calhoun's experiments could never be run with humans, a psychiatrist friend of mine suggested that just such an experiment may have already been unintentionally run: The Kowloon Walled City - a high-rise squatter camp located within Hong Kong but under Chinese authority. Essentially ungoverned, by the 1980s there were 50,000 residents living in 6.4 acres (about 5 American football fields or two average sized Costco stores.) With no building codes, a vibrant drug trade (with the concomitant public health problems), and unwritten laws enforced by competing gangs, Kowloon wasn't just ungoverned, it was lawless.

There's still a lot of room - if you will - to challenge how well the Kowloon Walled City generalizes to human populations. Cultural differences and historical evolution of the space are just a few variables that come to mind. But at the very least it makes the jump from rodents to human beings and suggests that the capacity and capability of our "conceptual space" described by Ramsden and Adams is substantial. Indeed, most of the constraints that defined Kowloon Walled city were conceptual - most related to cultural and sovereignty issues - rather than physical.

One of the more interesting aspects of Calhoun's experiments are the physical constraints he imposed in order to shape behavior. He used electrified fences to place specific limits on how rodents could move about the pens. The pen walls were covered with galvanized metal to prevent rodents from escaping. The design and placement of the food hoppers and drinking troughs shaped the social habits of each population.

This led me to wonder what types of constraints could be placed on a human being's conceptual space that might drive them to a similar behavioral sink. What might be the mental counterparts to electrical fences, unclimbable metal walls, and physical social attractors like food and water? More importantly, what can we do to mitigate the adverse or pathological effects of the conceptual constraints?

I'll consider the effects of two domains from what could be a long list of contemporary constraints on our conceptual space. Each of these, in my view, are symptomatic of the slide toward a larger social/cultural behavioral sink. I'll consider why this matters and what we can do, as individuals, about these constraints.

The University Experience2

"When people censor themselves they're just as likely to get rid of the good bits as the bad bits." - Brian Eno

The constraints being placed on the "network of ideas and technologies" on college campuses offer a cornucopia of food for thought. For several decades now, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE)3 has been documenting (and fighting) the erosion of free expression and academic freedom on college campuses. Vague and ideologically motivated policies crafted by unnamed and unaccountable administrators and committees have resulted in unprecedented levels of self-censorship among students and faculty.

It shouldn't surprise anyone that ideas taught to young minds in academia are carried forward into business, politics (as in law-making), entertainment, journalism, medicine, research, and many other areas of adult life. For the most part this is a very good thing. But when untested ideas or theories are taught as fact in a vacuum created by censorship and repression of free inquiry, the result is a fragile world view and a cascade of unintended consequences when real world constraints come into play. Efforts emerge to coerce the wider world to conform to the artificial world view professed by the university experience. Real world examples of this process include the pervasive cancel culture and DEI initiatives.

Wishful Thinking as a Scientific Methodology

I want to narrow the focus on campus culture to the adverse effects of it has on how scientific inquiry is practiced.

Currently, about US$800 billion is spent on research and development in the U.S. each year (NCSES, 2023). Most research funding comes from corporations and is focused on near-term commercial possibilities. Depending on which data you look at, about US$20 billion comes from institution of higher education and US$130 billion from the Federal government. The majority of basic research occurs in academic institutions. The Federal government's contribution dominates research in social sciences and humanities.

This type of spending is conducted by thousands of researchers and in the academic world they are driven by a perverse incentive known to insiders by the "publish or parish" aphorism. In a beautiful example of Goodhart's Law, academic researchers work to advance their careers by prioritizing the number of publications over quality of research.

And what is there to show for this incentive?

Since 1996, at least 64 million academic papers have been published (Curcic, 2023). Over the past five years there has been a 23% increase in the number of academic papers published. Each year more than 5 million papers are published in more than 46,000 academic journals.

The sheer volume alone is enough to explain why so little research is validated via replication - an important element to scientific inquiry. There's no money to be made in replicating so very little of it is completed until years later, if at all. Without question, this means there is a growing percentage of error in the corpus of scientific knowledge. Some of this error can be thought of like technical debt in software where prior code becomes obsolete and needs to be updated. Some of this error is also corruption and reflects deliberate manipulation of results in the interests of passing peer review and being published.

It's clear the emergent Kafkaesque environment on college campuses combined with the toxic incentives that drive research in most academic disciplines are corrupting the very science we will rely on to solve many of our most pressing social and technical challenges.

Like code reviews for software, there are a few intrepid researchers who take a closer look at published research. Sometimes this leads them to question the results and call for a retraction of the published article. On a percentage basis one would expect the number of retractions to increase along with the rise in overall publication volume. In 2013 about 1,600 research papers were retracted. The number of peer reviewed research papers retracted in 2023 after research flaws and fraud had been exposed by watchdogs from outside the system exceeded 10,000 (Van Noorden, 2023). On the face of it, this looks bad. Probably because it is. But there's more to the story.

That a paper would be retracted isn't in itself problematic. This is, in fact, how science works. We learn new things and if previous work is proven false or if unintended errors are discovered, they should be called out. This is how the "technical debt" of scientific research is removed. To not do so would be antithetical to the scientific process.

However, the growth in numbers of published academic papers and the journals in which they are published has two associated trends that are concerning. The first trend is the number of articles retracted due to deliberate misconduct. One study has shown that "67.4% of retractions were attributable to misconduct, including fraud or suspected fraud (43.4%), duplicate publication (14.2%), and plagiarism (9.8%)." (Fang, et. al., 2012)

Choosing from among many, a tragically ironic example involves Harvard professor Francesca Gino, known for researching dishonesty and unethical behavior, who has been accused of falsifying data. According to The Atlantic (2023), when then graduate student Zoé Ziani raised questions about Gino's research, several members of her dissertation committee "refused to sign off on her degree if she did not remove criticisms of Gino’s paper from her dissertation." Three independent data scientists - Joe Simmons, Leif Nelson and Uri Simonsohn - also found significant issues with Gino's research.

A subsequent Harvard investigation determined that Gino “engaged in multiple instances of research misconduct” in at least four papers, each of which has since been retracted. According to the Wall Street Journal, (2024) the investigation report "recommended that the university audit Gino’s other experimental work...and place Gino on unpaid leave while taking steps to terminate her employment." Gino is now suing her critics and to my knowledge has not fully disclosed her notes, data, and methods.

But the issue isn't resolved with the retraction of papers that are found to be faulty or fraudulent. A second concerning trend is that retracting a paper appears to have only a marginal effect on how frequently it's cited by other researchers. (Hsiao and Schneider, 2022) That less than 6% of the post-retraction citations would acknowledge the retractions for biomedicine research, where presumably the editorial oversight is much more rigorous and verifiable, suggests that the corrective influence of retraction is vanishingly small in other less empirical fields of study. The volume of research combined with archaic curation practices is facilitating the persistence of faulty or fraudulent science.

It's clear the emergent Kafkaesque environment on college campuses combined with the toxic incentives that drive research in most academic disciplines are corrupting the very science we will rely on to solve many of our most pressing social and technical challenges. More importantly, these factors have imposed significant constraints on the conceptual space available to our younger generations with whom our hope lies for finding innovative solutions. It's disturbing to see how the majority of practitioners in many disciplines are willing accept the "electrical fences" foisted upon them by a few ignorant bureaucrats and activists even though they may express privately how damaging such constraints are to their chosen fields of inquiry. How many other Zoé Ziani's are there, cognizant of problematic research yet vulnerable to entrenched toxic hubris embodied by tenured professors, academic advisors, and dissertation committees?

Laws, Laws, and More Laws

The actions of our lawmakers reveal a plethora of constraints placed on our physical and cognitive space. Research by Brian Libgober (2024), determined there are 49,746 federal laws spanning 1789 to 2022. Each state, of course, has their own set of laws and regulations. According to U.S. News & World Report (2020):

Across the U.S., state regulations contain 416 million words – more than 23,000 hours' worth of reading – and more than 6 million of those words are regulatory restrictions, or instances of such things as "must," "may not," "prohibited," "required" and "shall."

Add to this all the criminal laws defined for each state. Given these numbers and the fact that laws across the country are constantly in flux, "knowing the law" is an impossible task. And yet, we're expected to know all laws and regulations, because ignorance of them isn't a defense.

When we elect someone to be a lawmaker we shouldn't be surprised when they get to work making laws. In a public service version of academia's publish-or-parish treadmill, it seems you haven't earned credibility as a lawmaker until you've managed to make a new law and have it entered into the books. (What we sorely need is an additional house of Congress dedicated to un-making laws. But that's a subject I'll leave to the constitutional law experts.) And, of course, this filters down to local government bureaucrats tasked with fleshing out laws with supporting regulations. Regulators are going to make regulations because that's what they were hired to do and they do want to keep their jobs.

The mind-boggling number of regulatory "electric fences" is creating at least two outcomes that are most likely unintended. First, a learned helplessness response in people who would normally be inclined to take the initiative and engage in "risky" endeavors like starting a business or marriage or raising a family. Second, a move toward lawlessness, in spite of the ever increasing number of laws. As a generalization, the former outcome is the rational response of people whose character is inclined to follow rules, obey laws, and expect to suffer consequences for failing to do so. Escapism and withdrawal seem to be the most prominent response with this group for dealing with the incongruity. The latter is the rational response of a much smaller but much more influential cohort who recognize the selective application of law and therefore pick and choose the laws they will follow. Aggression and a preference for social disorganization seem to be prominent characteristics of those who follow the lawless path.

There are, of course, many other factors involved in each response as well as the degree to which any single individual will follow the respective paths. But both reflect the erosion of trust in the social institutions we expect to hold the higher ground.

Near-Term Prospects for the Law and Academia

Both the law and academia have a powerful and enduring influence over our culture and society. I think of them as large blunt objects in motion, fundamentally driven by primal human impulses - power, fear, and tribalism to name but a few. No single person is in control, but thousands of small incremental pushes by people who want a place on the train help build and sustain the speed and momentum. Both the Law Locomotive and the Academia Locomotive have considerable momentum to carry themselves forward on the tracks they've laid down. But their respective prospects are somewhat divergent.

[W]e're awash in an infinite sea of data. The more we create, the less we can trust anyone (or any system) that claims to have connected all or any of the important stuff. In this respect, it's all misinformation. It's just that some connections are more useful than others.

The Academia Locomotive is showing signs of losing steam. According to the Brookings Institution (2021), enrollment has been decreasing steadily since 2010, particularly among males. There are numerous reasons for this.

Parents and students alike are waking up to the considerable long-term debt burden required to obtain a four year college degree.

As noted previously, university administrations have carefully curated a campus culture that is increasingly adversarial toward free expression and open inquiry.

The very idea of accreditation is being recast since it's become so much easier to acquire the specialized skills required for most knowledge worker positions. In fact, universities cannot educate future knowledge workers at the pace required by 21st century business. The value of much less expensive and time consuming certifications and micro-degrees are supplanting the need for the traditional four year college degree.

In recognition of the previous point, more and more business and governments are removing the requirement for a college degree from many of the jobs they offer, thus removing the incentive for pursuing a college degree.

These and other factors are slowing down the Academia Locomotive, but losing its Crazy Train status isn't going to happen an time soon.

The Law Locomotive, however, appears to be full steam ahead and is much more likely to jump the tracks and precipitate a state of lawlessness. As many practicing attorneys and law professors have noted, laws aren't in place to protect the public from criminals. If they did, there would be no crime. Laws are in place to protect the criminals from the public. An casual study of post-WWII Europe will reveal the degree of harshness average citizens are capable of when placed in a culture of vengeful lawlessness. Anger and grief place loose and irrational borders around what qualifies as just retribution.